A transatlantic cruising log by Norman Fullam

Having met fellow Howth members Tony and Linda Olin in Greece last month, Norman Fullam has posted this great account of his trip across the Atlantic in his Cape Dory 30C in 2013. It was written some time ago for a friend in America who was interested in hearing about how he got on during the trip. Norman is a recently joined member of HYC, introduced by his friend John McMonagle, who accompanied him for most of the trip. (John owns Avanti, an Island Packet 32 in HYC.)

'Dolphins in the Dark' - Norman Fullam

An email arrived just as we were about to go down the road to dinner in a friends house. It was from Sean in Marsh Harbour in the Bahamas asking if I would crew with him on his Cape Dory 30 on a transatlantic voyage to Dun Laoghaire in Ireland.

I knew the boat well having taken her from New York down to the Bahamas and back to Florida last year. I liked the boat so much that I had spent the winter trying to buy something similar on this side of the pond. Indeed, I had looked at five Hallberg Rassy 29s in Scotland, England, Portugal and Holland, had two of them surveyed with contracts signed and deposits paid but the sale fell through on both occasions. I had turned down a request from Sean in January to bring the boat from Florida to the Abacos as I had just paid the deposit on a HR29 in Portugal and was on the way out for a sea trial at the time.

I mentioned the proposal to our friend at dinner who is an experienced sailor and had done the westbound ARC in a Swan 60 just last year. He told me I must be mad to even consider the trip in a 30 foot boat. But the seed was sown. The invitation had mentioned all the preparatory work already done for the voyage. This included fitting a Cap Horn self steering unit, all the fuel and provisions and the purchase of a SPOT satellite tracker. However, the clincher was the provision of the Appleton's rum. Later that night after a good dinner and fine wine I emailed my acceptance, contingent on the provision of a long range two-way communications system, additional strengthening for the extra wide main hatch on the CD30 and a third reef point in the main.

The deal was done and in late April 2012, I flew to Marsh Harbour via London and Nassau and joined Blue Caribbean at the Jibroom Marina. There, I fell in with a really nice group of cruisers who had been assisting Sean for the previous two months in getting the boat ready. I also heard about a boat Common Sense planning to leave shortly for Bermuda intending to join the eastbound ARC Europe Rally bound for the Azores and Lagos in Portugal. I made contact with the Australian owners Terry and Carol over in a nearby marina and we agreed to keep in touch on the way up to Bermuda. When I told them that I had done this trip about ten years ago from Antigua, Terry asked me what I considered the most important qualification to have on board for an extended transatlantic voyage. Without hesitation, I replied that a "fixer" was the key person needed. Things will fail and break on such a long trip and there are no handy boatyards to nip into on the North Atlantic. The wherewithal to keep the show on the road must be carried on board and this includes both spares and expertise.

Our fellow cruisers gave us a farewell dinner the night before departure and were back next morning at 1100 on Tuesday 1st May to see us off. Michael from Ottumwa, Iowa, produced a bottle of malt Scotch and we all offered a toast to that unforgiving god of the sea, Poseidon. Michael's townsfolk are known for their foresight. We took a wee dram each and returned it to the ocean unswallowed. (Some sailors I know from Donegal might take grave exception to that last bit.)

Our fellow cruisers gave us a farewell dinner the night before departure and were back next morning at 1100 on Tuesday 1st May to see us off. Michael from Ottumwa, Iowa, produced a bottle of malt Scotch and we all offered a toast to that unforgiving god of the sea, Poseidon. Michael's townsfolk are known for their foresight. We took a wee dram each and returned it to the ocean unswallowed. (Some sailors I know from Donegal might take grave exception to that last bit.)

A short run across the Sea of Abaco brought us to Man O'War Cay where we picked up the mainsail from the local sailmaker. He had declined to put in the cringles for the third reef, stating that if the wind got that bad, we should just take it down. I obviously hadn't made myself fully clear in that my reason for the third reef was to make extended runs in marginal conditions without putting the rig under undue pressure. The boat, rig and sails were thirty years old and a four thousand mile passage across the North Atlantic was not going to be easy on them.

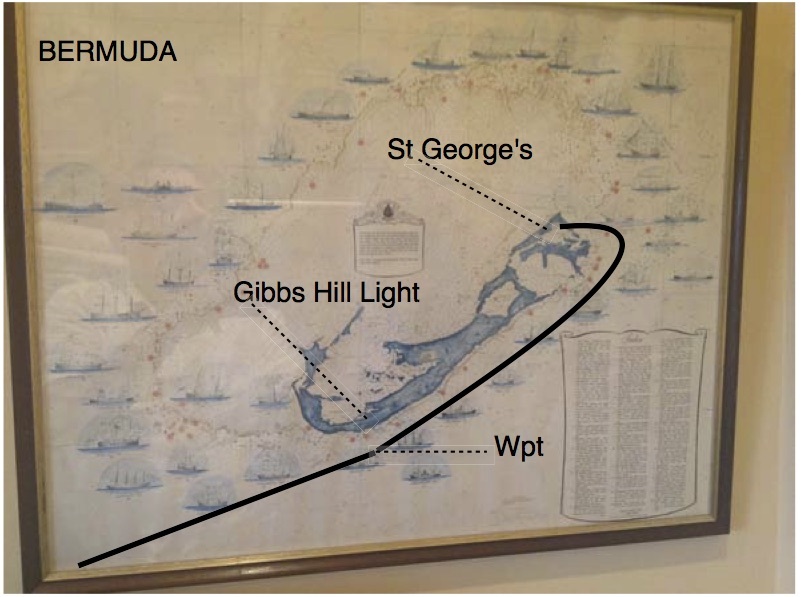

We had planned to depart the following morning more or less in company with our Aussie friends on their Catalina 42, but took the opportunity to weigh anchor and run the inlet at 1800 and get some miles under our belt. After a very bouncy passage through the inlet, we bore away to the Northeast and set sail for our waypoint off Gibbs Hill Lighthouse in Bermuda, just over 730 miles away. The seven day forecast for light winds meant that we should get there in a week, motor-sailing as necessary to maintain a steady 5 knots.

Things went well for the first few days. We settled into the watch system of three on, three off during the night hours followed by a four on, four off during the morning and afternoon with a couple of two hour dog watches in the late afternoon before the cycle started all over again. Sean liked to use the Cap Horn self steering during his watches but I favoured manual steering on the wheel during mine. There was no other auto pilot on the boat. Sometimes I wonder if I am out of step with the majority of the sailing community who consider a wind vane or an autopilot essential for even relatively short passages. I favour manual steering on my feet for several reasons. It keeps me constantly in touch with all the influences and nuances of wind, sea state and sail settings; it helps keep me awake and most of all, it helps me obey the prime rule of seafaring in keeping a sharp lookout at all times. Obviously auto pilots are very useful when its necessary to carry out some essential task on board when no one else is available to take the helm but I just cannot fathom someone with responsibility for the watch down below reading a book or sleeping. During my career in the Coast Guard, I estimate that at least thirty of those who died tragically at sea around the Irish coast did so under those precise circumstances. Many more suffered collisions or groundings but got away with it.

With the expected light winds we were motor sailing most of the time and conditions were good. The revs were increased to maintain a steady five knots and we were nicely into our routine. In the very early hours of day three, I was on watch when a lone dolphin came calling. He powered in from the port side and dived under the hull below the bridge deck. Time and time again he repeated that exact same manoeuvre. I say he, because I fell into a reverie thinking of my old friend and former shipmate Mike who was from Bermuda and had passed away just a few years ago. His ashes are scattered at North Rock Lighthouse on the outer reefs off Bermuda. I had learned a lot about seafaring, navigation and above all, seamanship from Mike when we were young men sailing these waters together on board the freighter Somers Isle and we maintained our close friendship over the years. Now, I wondered if there was some spiritual or mystical connection between Mike and this purposeful dolphin diving under our hull at the exact same spot every time. Was he telling me that we were together again for one more trip and that he would be there for me as ever on this wide ocean? The dolphin disappeared and the watch changed at 0200. I had one leg through the hatch on my way down when I thought I detected an almost imperceptible change in the engine note. I looked behind and saw Sean rigging the Cap Horn control lines on the steering wheel and thought he must have brushed the binnacle mounted throttle lever. Moments later, climbing into the bunk, a more distinct cough from the engine and I called to Sean to shut it down which he did instantly. I climbed back out to the cockpit, opened up the port locker and looked at the fuel gauge located on the diesel tank mounted just under the bridge deck and sure enough it was bouncing off zero. A quick top up of fuel and Sean cranked the engine a few times without success. There was some wind so we sailed. At daybreak, Sean who is not just a very good sailor but a brilliant "fixer" on a boat got to work and changed out the fuel filters and set about bleeding the system on the old but recently fully reconditioned Volvo MD7a. Nonetheless, it still refused to start. I had a go for a while and decided to get some rest at 1100. I studied the manual in my bunk and at 1300 methodically resumed the effort, laying out all the tools as I had seen Frankie, a wizard engineer friend of mine do on many occasions on previous trips. The engine kicked into life at 1436 and we were back in a comfort zone. Our failure to check the fuel gauge could have resulted in a three week 500 mile sail to Bermuda in present wind conditions or an ignominious return to Marsh Harbour under engine because of our heavily depleted fuel. Next day our weather forecast from Mary in Dublin indicated that the very light and variable winds were due to move onto our nose from the NE. A change of strategy was required to make it to Bermuda. Had the dolphin in the dark been trying to warn me to check the fuel gauge ? I really think he was.

Approaching dusk later that same day Saturday May 4th, the AIS receiver proved its worth on the first of many occasions during the trip. It picked up the transponder of an 800 foot tanker coming out of the setting sun 4 miles behind us on the port quarter. The AIS told us that his CPA or closest point of approach would be 0.3 of a mile. This would be a little too close for comfort with such a large and unmanoueverable vessel, so I called him up on the VHF radio and was very glad that I did. Normally in such circumstances and without the benefit of AIS, even with the right of way as we had, the prudent move from a small sailboat would be to alter to starboard and give the big guy as much sea room as possible to allow him continue along our port side. When I informed the ship of our presence and intentions, the watch officer told me to stand on my course as he was approaching a waypoint and was just about to make a course alteration to starboard on his way to Europe. A former colleague who is an experienced sea captain spent many years in the busy English Channel and could never understand why yachts and small boats would not hold their course when encountering his ship even when the small boat had the right of way. He told me he always had them in sight and fully intended to follow the international Colregs procedures. That might be sound in the English Channel with traffic all over the place and everybody on full alert but it has rarely been my experience in the open ocean for big ships to give way to small pleasure vessels.

Soon afterwards, the sun went spectacularly down astern and the moon came up dead ahead just like two great big glowing golden balloons on a seesaw. The exact opposite happened next morning at dawn. Now we were into the Sargasso Sea shuffle big time with the light fluky winds forcing us to tack and put up and down sails repeatedly. The pinpoint accurate forecasts from Mary in Dublin really came into their own. We were able to sail to the northwest and motor back east to find more wind to sail again, thus allowing us to manage our dwindling fuel supplies.

By Monday morning, nearly a week out from the Bahamas, we still had 212 miles to run and the increasing NE trend in the weather was pushing us further to the west of the rhumb line track to Bermuda. At noon, the log records NE winds increasing 15 to 20 knots with lumpy grey seas and wet conditions under double reefed main and staysail. We were heading 143T at 3.8 knots but our VMG (speed towards destination) was only 0.7 knots. Soon we would tack yet again where we could make better speed and VMG, but the progress was always worryingly towards the NNW and the dangerous reefs to the west and north of Bermuda.

By 1400 next day Tuesday, we found ourselves 23 miles NW of our track line, 130 miles out from destination with the wind rising to 25 knots. It was forecast to come around to the ESE next day. Sean proposed skirting the entire chain of reefs to the west and north of Bermuda and coming in to the approach channel near St Georges under engine from the NW or Canadian side of the islands. I have a chart at home showing 40 of the most notable shipwrecks around Bermuda. 31 of them were along that route. We tacked and headed SSE and at 2200 got east of the rhumb line for the first time all trip.

By midnight we were doing 7.4 knots and flying. Next day we tacked along the rhumb line and  blew the staysail with 100 miles to run. Later we got the Yankee up for a while but the winds were getting up to ESE 30 knots so we took it down. By 2000 we were far enough to the east of the rhumb line again to lay our destination waypoint at the south of Bermuda off Gibbs Hill Lighthouse. We went for it under reefed main and engine and the Cape Dory revelled in the conditions, taking the ever increasing seas nonchalantly in its stride.

blew the staysail with 100 miles to run. Later we got the Yankee up for a while but the winds were getting up to ESE 30 knots so we took it down. By 2000 we were far enough to the east of the rhumb line again to lay our destination waypoint at the south of Bermuda off Gibbs Hill Lighthouse. We went for it under reefed main and engine and the Cape Dory revelled in the conditions, taking the ever increasing seas nonchalantly in its stride.

Next morning at 0500 Thursday 10th May, we stopped the engine and hoisted the Yankee in 25 knots from the ESE. We were flying. The Raymarine plotter recorded speeds of up to 8.3 knots before it failed due to an antenna problem. We got pooped crossing the Challenger Seamount at 0700. A few bucketful's went through the hatch and landed on Sean's bunk. He was in it at the time. The cockpit drained quickly and at 0745 those most magical of words after ten days at sea:- LAND HO !!!!

We cruised safely along the south shore in marvellous sailing conditions looking at all the beaches and white roofed houses in their myriad of pastel shades. A chart from 1738 of the islands refers to this coastline - "This Coast is the Boldest of Bermuda & in some Places the Largest Ships may with Safety come within half Gunshot of the Shore." Of the other side, the same chart says "Off this End of the Island from S.W. to W.N.W. are great number of Rocks at 3 or 4 Leagues distance from the Land whereby abundance of Ships have been lost." We checked in with Bermuda Radio and received our instructions and clearance to enter the Town Cut at St George's and present ourselves to customs and immigration on Ordnance Island. We completed all the formalities and went to anchor close by. We shut the engine down at 1400 Bahamas time or 1500 local. The first leg of our voyage was over.

Bermuda is a place close to my heart. I first went there in 1968 as a young radio officer on the RMS Escalante, a cargo liner flying the Pacific Steam Navigation Company house flag outward bound from Liverpool for the Caribbean and South America. It was my first trip to sea and St. Georges was my very first port of call. A year later I was back for the first of many visits on another PSNC vessel Somers Isle. She was called after the original name for the islands which were settled after Admiral Sir George Somers was shipwrecked in 1609 on a shoal just outside what is now St. Georges. He was bound for Jamestown in Virginia bringing relief to the settlers who were in a bad way at the time, ravaged by harsh winter, hunger, disease and Indian attacks. Sir George and the entire complement of 150 souls made it ashore to the uninhabited islands without loss of life. Over the course of nine months they built two small vessels Deliverance and Patience from the wreckage of their flagship Sea Venture and the islands' famous cedars and subsequently went on to relieve the Jamestown garrison. This enabled the settlement there to survive and later grow and develop into what would become the modern USA. Sir George returned to Bermuda later in 1610 and died soon after from eating a surfeit of wild pig. His heart is buried in Bermuda and his pickled body was brought home for burial in Dorset.

I first learnt to sail with Jim, a young Bermudian cadet on the Somers Isle whose family had an  elegant wooden 30 footer. She was a lovely boat and he was one of the best sailors I've ever sailed with. Bermudians were recognised as world leaders in sailing at the time.

elegant wooden 30 footer. She was a lovely boat and he was one of the best sailors I've ever sailed with. Bermudians were recognised as world leaders in sailing at the time.

Sean had the Raymarine plotter fixed in jig time and we brought the staysail ashore to a sailmaker close by the dinghy dock and we were on shore leave. All that remained to be done for the next leg was some laundry and take on fuel and provisions.

My friend Ellie, Mike's wife, picked us up after she finished work in Hamilton and we went to her house on nearby St Davids Island for obligatory rum and gingers, the first of very many over succeeding days. Indeed we spent a very pleasant weekend up at the house with Ellie and her family. It was great to have an ensuite shower in my room and to sleep in a real bed again. Over the course of the weekend, we got all our laundry and provisioning done and picked up the repaired staysail. On Sunday evening, Ellie and the new man in her life Laurence, dropped us back down to the boat ahead of our planned departure for the Azores at noon on the following day. We wanted to get away ahead of the ARC Europe Rally fleet which was due to depart for Horta two days later. All we needed to do were some final preparations on the boat and take on fuel. I was also hoping to make a quick visit to Bermuda Radio and touch base with the operations manager there who was a former colleague from the Irish Coast Guard. If time allowed we were going to have a swift beer with our Aussie friends from Common Sense who had arrived in Bermuda 36 hours behind us. They were ensconced with most of the ARC Europe fleet over at the local yacht club. Laden with final provisions including two new five gallon diesel cans, we dinghied out to the boat and turned in for the night.

At breakfast on Monday morning Sean told me that he had changed his mind about taking the boat to Ireland. A major transatlantic voyage was not now what he wanted to do. Instead, he planned to take the boat back to the Chesapeake and put it for sale. It was a 600 mile trip and we should be able to fly home from the US in two weeks time. It was disappointing but not entirely unsurprising news. During our trip up from the Bahamas, I sensed at times that Sean was not entirely at one with the spartan conditions and rigours that come with sailing a small boat far out on the Atlantic ocean. In such circumstances, the prospect of a further 3,000 miles on the ocean just did not attract him. Better to decide now rather than 1,000 miles down the track.

That very apt Irish phrase - Tog go bog e came to mind - Take it easy. And we certainly did. I couldn't think of anywhere better in the entire world to spend a few days than here in Bermuda.

We went over to the yacht club in the dinghy to hook up with the crew of Common Sense, but they had gone to Hamilton for the day. We met them later and learned the Catalina 42 had encountered serious difficulties with the sea conditions in the last 100 miles and suffered a full knockdown at one point. The place was a hive of activity for the ARC crews and organisers. We had a second breakfast and watched the goings on. There was an owner beside us making lengthy calls in Italian to someone trying to locate and recruit crew for the voyage. I went through the same thing twelve years ago in the exact same place when I did the Arc Europe aboard Aine. One of our crew departed unexpectedly and we spent several days without success trying to locate a replacement. I knew there would be crewing opportunities and the thought did cross my mind to seek a berth. However, I had accepted Sean's invitation in the first place because I really liked the Cape Dory and was confident that we were both up to the challenge. I liked the boat so much that I had spent the winter traveling around Europe looking to buy a Hallberg Rassy 29 which was very similar in design and layout to the Alborg designed Cape Dory 30. Besides, I would not embark on such a demanding voyage unless I knew either the boat or the owner very well.

Meanwhile, I had to arrange a US entry visa. This was now necessary on account of arriving by private sailboat. The process is very detailed and would take at least five days. Sean figured that as he was still within 90 days of his last entry to the US by air, his ESTA visa waiver was still in force. While waiting for my scheduled interview at the US Consulate in Hamilton, we went to Gates Fort on the Wednesday to see the ARC Europe fleet depart through the Town Cut and cheered on the three Irish boats and our Aussie friends on Common Sense. One of the Irish boats came through the cut just ahead of Outer Limits, a Dutch Hanse 37. Three days later, Outer Limits hit an underwater object, thought to be a whale and began to take water. The four crew were forced to abandon ship. They were rescued by a freighter heading for Sardinia.

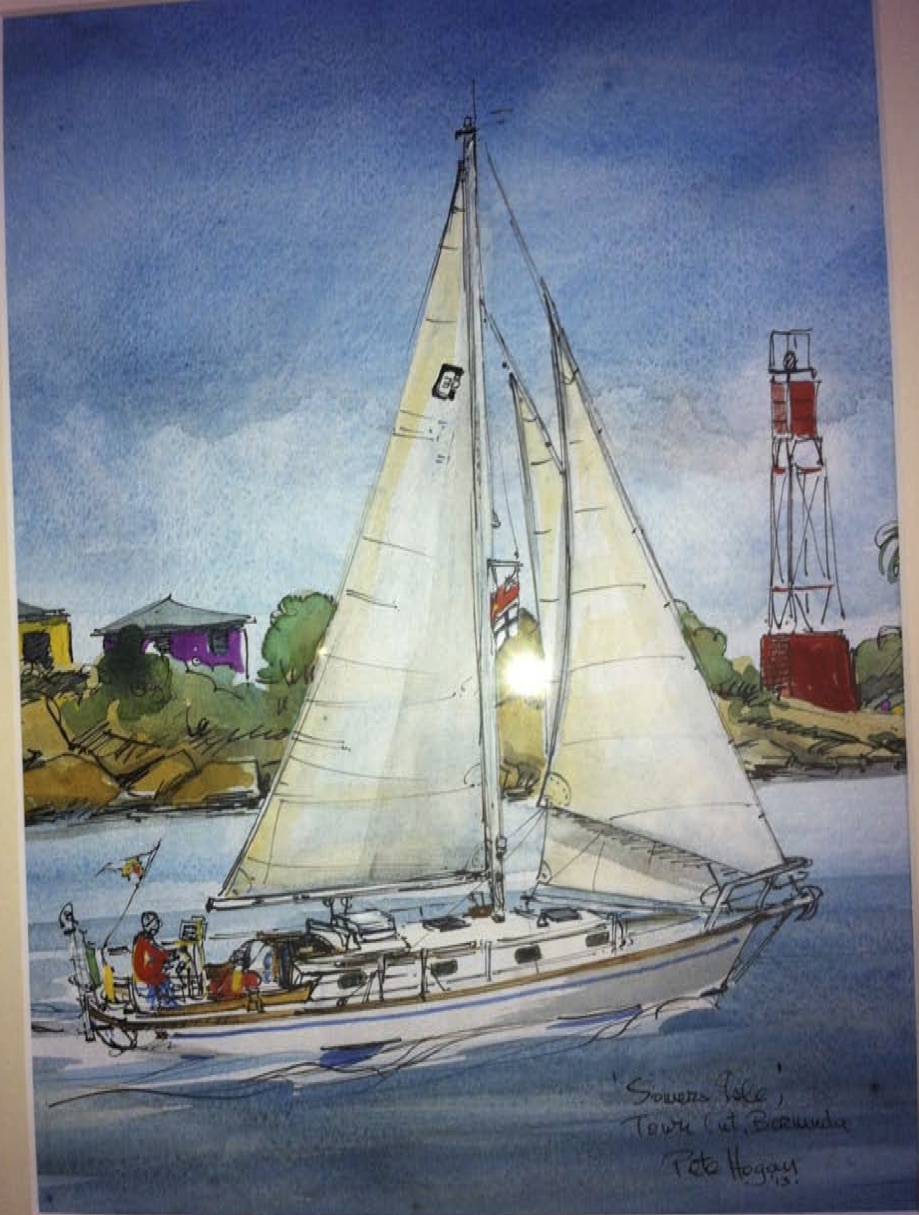

By that stage, I was fully confident that the Cape Dory was well fit for the north Atlantic transit  and when John back home in Ireland agreed to come out and crew for me, Sean and I struck a deal for the boat and he flew home. I resolved to change the name to Somers Isle when we got to Europe.

and when John back home in Ireland agreed to come out and crew for me, Sean and I struck a deal for the boat and he flew home. I resolved to change the name to Somers Isle when we got to Europe.

After 10 days in Bermuda, Blue Caribbean, departed for Horta in the Azores 1,800 miles away to the NE. We now had a couple of extra diesel cans on board with a supply of 60 gallons of fuel in total. The first tropical storm of the season, Alberto, was tracking up the US coast 600 miles west of us and producing some dirty weather in our locality. We got away from the quay in 15/20 knots of fresh easterly winds and got set up inside the shelter of the harbour before venturing out into some very lumpy seas indeed. The middle finger on my left hand got badly crushed while rigging the lines from the Cap Horn self steering. It caught between the jam cleat on the wheel and the gear lever. A return to Bermuda for medical treatment looked on the cards, but there is a very comprehensive medical kit on board and I managed to patch it up and keep it free from infection.

The plan as before, was to maintain an average of 5 knots using wind or engine as appropriate. After a few days of decreasing winds, I modified this to 4 knots when I looked at fuel consumption rates, forecast winds, provisions on board and distance to run. Sean, now back home in Ireland was giving us the daily weather by text over the satphone which was really great. We kept a particularly sharp lookout for the hulk of Outer Limits as it had not been confirmed sunk. Close to its last known position, I was talking to John from the wheel when a large whale breached over his right shoulder less than a cable off the starboard beam. It was an amazing sight. I had seen whales on the surface before but they always seemed to travel in slow motion. This one came clear out of the water like a leaping salmon. I shudder to think what would have happened if it had hit full on. It was easy to understand how a whale could casually sink a boat as probably happened with Outer Limits. Mother Carey's chickens flew continuous escort for several days above glassy seas as we sailed towards and over the New England Seamounts. A big bright rainbow lit up the dawn sky on 27th May, an auspicious omen for Jennifer, daughter of a longtime sailing friend back home, who was getting married later that day. We sent a good luck message to the newly weds by satellite but don't think it got through.

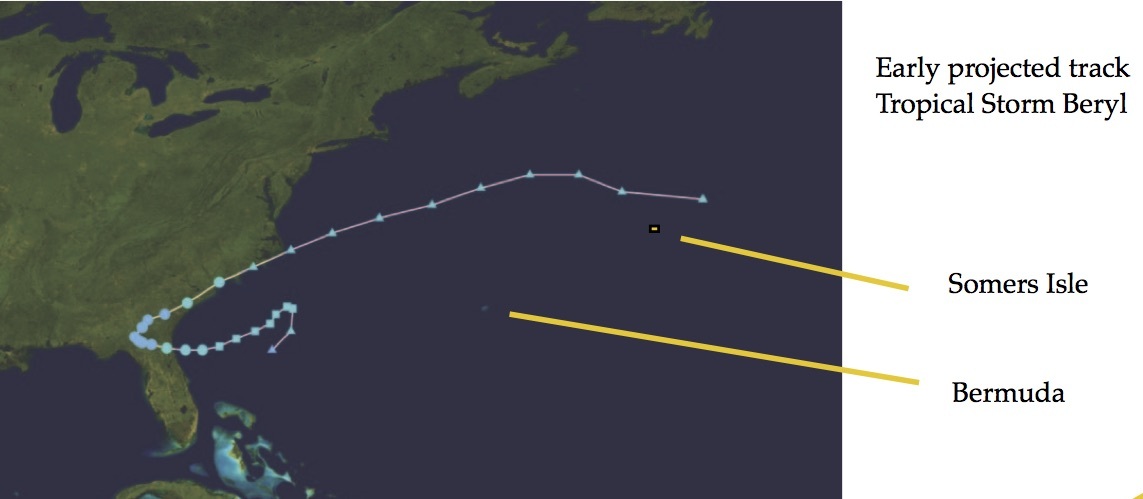

Worried about decreasing winds on the southernmost route to the Azores, I opted to move North a whole degree to latitude 36 degrees N. before turning east for the Azores in an effort to get more wind. This took a day and about 6 gallons of diesel. Just after the course alteration, the forecast gave a new tropical storm Beryl passing 300 miles north of our track in 3 days time. This was fine by me as we should get a nice blow from it and still be far enough away for safety.

Next day just before noon, an Island Packet 35, Freedom Found overtook us heading SE. This was strange. We had left Bermuda ahead of him. Our joint destination, Horta, lay to the NE. He was a straggler in the ARC Europe Rally and I knew that he was getting specialist weather routing from England. Was there something he knew that we didn't? I tried calling him on the radio but he was having difficulty reading me. After sunset that evening, my good friend the dolphin returned, gambolling close aboard on the starboard beam. When he was sure he had my full attention, he bore away and streaked off to the SE at breakneck speed, dived and was gone. Moments later he reappeared and repeated the same manoeuvre. Hmmm! A certain unease accompanied me through the night.

Sure enough, when the forecast came in from Sean next day, it was apparent that Beryl had recurved again and was now going to pass right over us in 60 hours time with winds of more than 50 knots. My training and experience told me to head for the equator, but we were more than a week out on passage and heading south for 3 days in strengthening winds would leave us back near Bermuda in early June with all kinds of issues about fuel, provisions and the official start of the hurricane season. I headed for the equator alright but aimed to intersect it on a SE heading towards Nigeria - just as the dolphin had suggested the night before. We cleared everything possible from above decks and rigged the drogue ready for use on the longest rope we had on board. We tested the storm sail but found the slides were too big to fit our mast track.

Three days later when we had hauled to the SE of Beryl's track, we were wearing just the staysail when we got our worst of it at 35 knots.

Again the Cape Dory just marched on under the staysail without any fuss and we were very comfortable. It was tough to be heading away from our destination for so long after struggling north to get some good wind but as we ran to the SE, I made sure to keep at least a knot of VMG towards Horta, so there were 25 miles a day that we didn't lose.

Back on track and nearly two weeks into the passage, things started to break and fail as they inevitably do after any extended period at sea. The alcohol cooker started giving trouble; it's fuel was evaporating rapidly from the reservoirs. We lost a couple of buckets and winch handles, the compass fluid began to leak, we got a rip in the mainsail (fortunately below the second reef cringles) but the worst was yet to come.

Approaching midnight on June 4th, almost two weeks into the passage and 800 miles from our destination, my friend the lone dolphin turned up once more. This time he surfaced under the port rail, grabbed my attention, swam off purposefully to a spot four points (45 degrees) off the bow, climbed a wave and dived down off it into the depths. He repeated the exact manoeuvre at least six more times. What could it mean? The weather forecast was ok; the wind had finally come on to the perfect SW direction although it was quite rough at 18 knots; we were on course. Everything looked good.

At 0430 in the morning the staysail blew out. It was quite tricky on the foredeck getting the remnants down. Later at 0930 when John turned to, he informed me that a long dormant heart problem had recurred during the night. We set up an emergency consultation via satphone with his GP back in Ireland. The doctor was right on the case and able to advise on breathing exercises and rejig an appropriate prescription from John's supply of on board medications. What was that Dolphin on about, diving off waves in that particular direction?

Bang! At lunchtime the steering failed.

We knew where the emergency steering bar was but could we unscrew the protective armoured metal cap from the cockpit sole to get at the rudder stock? For thirty years that cap had welded itself unused, into its housing. A call to Sean on the satphone yielded the whereabouts of a special two pronged tool for unscrewing the cap but to no avail. It was jammed solid. I got down into the port locker and crawled under the cockpit sole and discovered what the dolphin had tried to tell me - Tighten up those lock nuts on the steering cable !

The port side cable termination on the Edson wheel steering mechanism had worked loose. It should have been held back tightly by the lock nuts to secure its angular run of 45 degrees out  around the quadrant. The slack cable had then slipped off the starboard pulley and jammed underneath it. This had put so much pressure on the port side pulley that its retaining pin had sheared off under the strain and the cable was a tangled useless mess. A repair job was technically feasible but rendered impossible by the uncontrolled steering quadrant scything about in the confined space under massive pressure from the sea outside on the rudder. Not alone were fingers at risk, the thing could have amputated an entire hand.

around the quadrant. The slack cable had then slipped off the starboard pulley and jammed underneath it. This had put so much pressure on the port side pulley that its retaining pin had sheared off under the strain and the cable was a tangled useless mess. A repair job was technically feasible but rendered impossible by the uncontrolled steering quadrant scything about in the confined space under massive pressure from the sea outside on the rudder. Not alone were fingers at risk, the thing could have amputated an entire hand.

Three hours later and we were no further on. The physical exertion of heaving gear and laden fuel cans around to get down into the lockers was immense, not to mention the strain of trying to lever the stubborn cap free. John's frame is too large to get down into the lockers but he stuck to the task of trying to free the cap so that we could get the emergency tiller in place. All thoughts of his heart condition were put aside. I don't know where he got the supplies of WD40 from but the decks were awash with it. At one stage we thought we might have to break through the deck with an anchor fluke to get at the rudder stock. Eventually his patience and persistence paid off and the stubborn cap relented and the steering flat below saw daylight shine in for the first time in three decades.

Now 750 miles out from Horta, we rigged the emergency tiller bar which also meant that the Cap Horn was out of action. I didn't mind too much but John was having difficulty steering at night as there was mist and dense fog at times for 4 or 5 days in a row and the compass card was now almost aground and impossible to read. As a result we had to lay ahull for several hours every night. This was a cause for concern as we could only make progress for 18 hours a day instead of 24 with consequent implications for food supplies and cooker fuel. What was meant to be a 15 day trip was now extending into the 20s. On the night of June 4th in dense fog we had a close encounter with a merchant vessel coming up astern. Once again, the AIS picked him up and when I contacted the vessel on radio, it was reassuring to hear that he already had us on radar and was altering course to keep clear. An additional comforting factor lay in receiving regular and accurate weather forecasts from Sean. We knew exactly where the wind was and could manage and conserve our diesel.

Three days out from Horta we passed over the spot where we buried Paddy Weadick from Arklow, the bosun on the mv Somers Isle back in December 1969. We were outward bound from London to Bermuda at the time and he was fatally injured when he fell while working on a high stage at wheelhouse level, down onto the main deck. It happened shortly after midday and his body was consigned to the deep at nine that evening with full ceremonial honours and all crew mustered on the poop deck. It was a sad end for a man who had gone to sea as a boy in the last days of sail and learned his trade aloft on the yards high up among the topsails, royals and gallants of old. We think he suffered a heart attack and fell. No such thing as inquests or post mortems in mid-ocean back then. I had asked John who is a teetotaller, to save our last can of ginger ale for the occasion and we drank a toast to his memory at dinner that evening, mine with a good measure of Appleton's Estate rum in it. I'm sure Paddy would have approved.

In the deep dark of that same night we were visited by two unseen dolphins, their presence apparent only from sparkling luminescent trails weaving in the water as they streaked in towards us from astern. A whole firmament of spectacular phosphorescence exploded at the confluence of their crossing beneath our transom and we seemed borne forward on their stellar wake. The chart plotter packed in later on but we were untroubled as we approached that exquisite moment in a long passage when we could motor all the way home, should it prove necessary. - It didn't.

Taking it easy on a plinth in Horta & a hundred metre volcanic hot tub for John in Sao Miguel .

We arrived in Horta after 23 days at sea having had something hot three times a day at every meal whether it was porridge and eggs for breakfast, soup at lunchtime and regular dinners in the evening. We had plenty of water and diesel and would not have starved for a while yet, but may have had to suffer a surfeit of fruit salads and cans of green beans for a week or so. We had lots of pasta but couldn't have cooked it because of the lack of cooker fuel. A good scouring of the seals in the cooker sorted the problem in port.

One that sadly didn't make it.

Irish Hallberg Rassy 48 'Elilijah' (left) leads Dutch Hanse 37 'Outer Limits' through the Town Cut, Bermuda bound for the Azores.

60 hours later, 'Outer Limits' hit a whale and sank. All 4 crew were rescued.

We got the repairs done and had some R and R in Horta before cruising to the beautiful neighbouring islands of Sao Jorge and Sao Miguel. Duncan Sweet and his cheerful team at Mid Atlantic Yacht Services in Horta were great. The charming Ilda even looked after all the complex details of the EU VAT importation process which went through without a hitch.

We then sailed the remaining 850 miles to Vilamoura in Portugal on a beam reach. A long ocean passage like that was not without problems. The gear shift cable broke. We lost the chart plotter again, then my standby handheld GPS, then the grab-bag GPS but we kept going on a little boy scout's Garmin Gecko. My big fear with that featherweight GPS was that it might blow over the side when laid down on the cockpit lockers to get a fix. We still had a very basic GPS on my Nokia mobile phone and a sextant in reserve. We could of course, always revert to good old dead reckoning navigation if the worst really came to the worst. We tore a few sails and I tore a knee cartilage but we got there in 8 days, finally transiting the vast Cap St Vincente traffic separation scheme under the old faithful Yankee and refurbished storm sail.

We laid the boat up in what seems to be an excellent boatyard in Faro for a few months. The plan for next year is to move on into the Mediterranean and sail the Odyssey which has been an ambition of mine for a while.

After that, Quo vadis.

Postscript: After my arrival in Portugal, I re-registered Blue Caribbean as the Somers Isle. It had always been my intention to buy a sailboat on my retirement from the Coast Guard and name her after my old ship. At the time of writing she lies on the River Guadiana at Vila Real de Santo Antonio in Portugal just across the river from Ayamonte in Spain.

John later commissioned a painting of our departure from Bermuda by the maritime artist and solo-circumnavigator, Pete Hogan and gave it to me as a memento of our voyage.

When I look now at the Somers Isle stretching for the open ocean like an eager young thoroughbred, the magnitude and the scale of what we had undertaken overwhelms me. ' My God, what a great little ship !'

Dedicated to Mike and all those other dolphins now sadly swimming in the dark, who help guide us errant sailors towards the light.

NF

21 February 2013

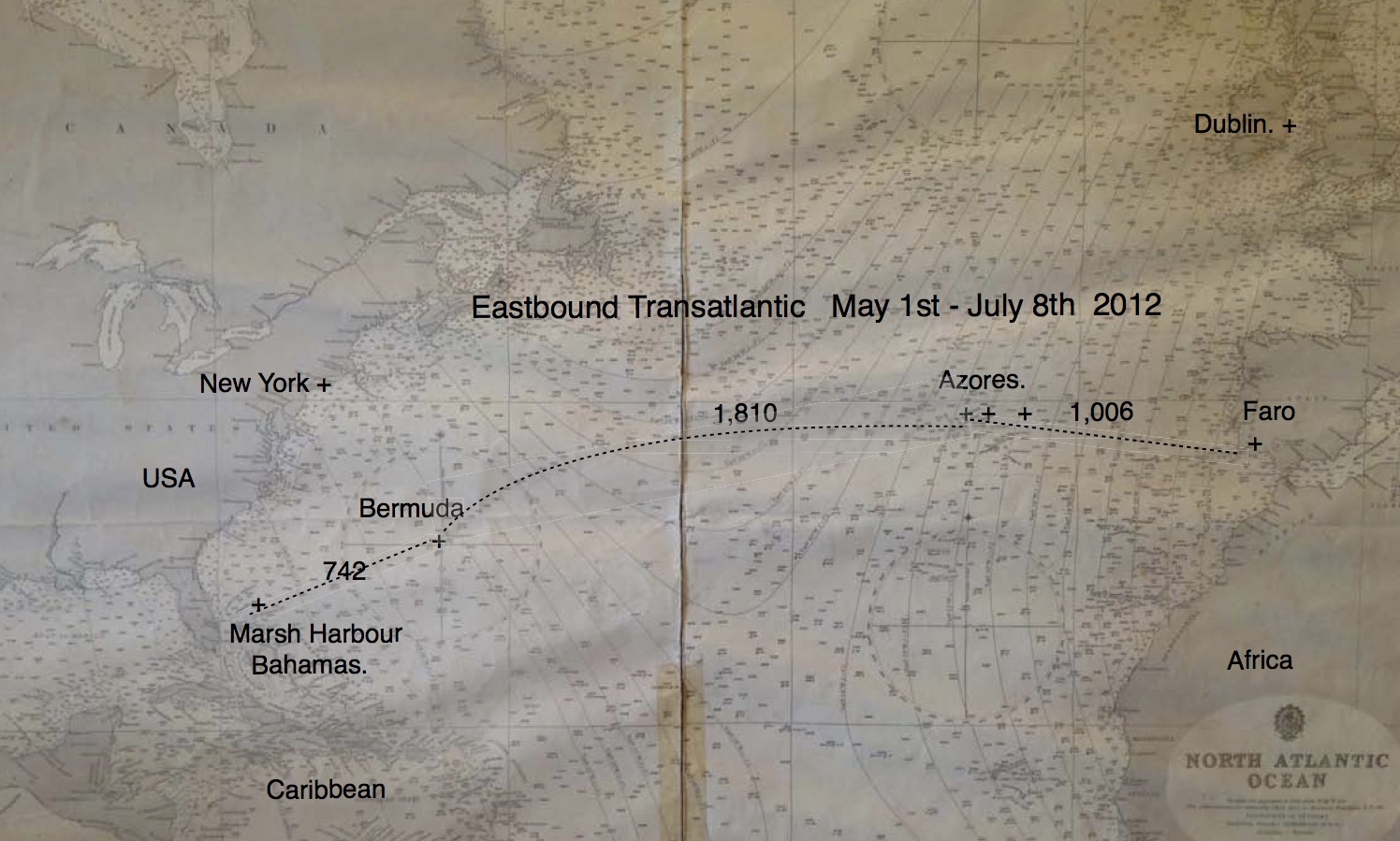

The track above is overlaid on the actual Admiralty passage chart used by the mv Somers Isle (left) of the Pacific Steam Navigation Company during multiple crossings of the Atlantic in the 1960s.

The track above is overlaid on the actual Admiralty passage chart used by the mv Somers Isle (left) of the Pacific Steam Navigation Company during multiple crossings of the Atlantic in the 1960s.

On close inspection, faded remnants of erased course lines and noon position plots drawn on the chart by successive second mates during those voyages are still evident.

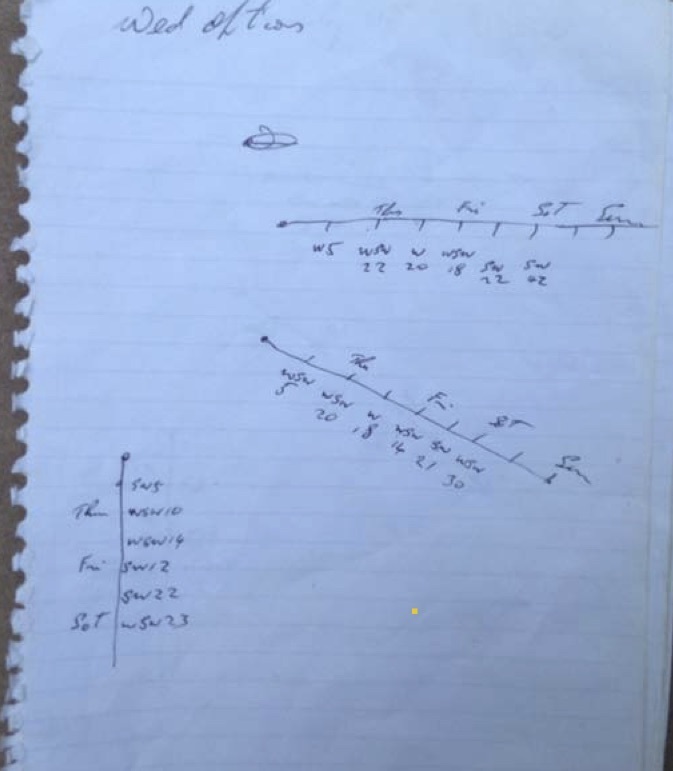

Weather:

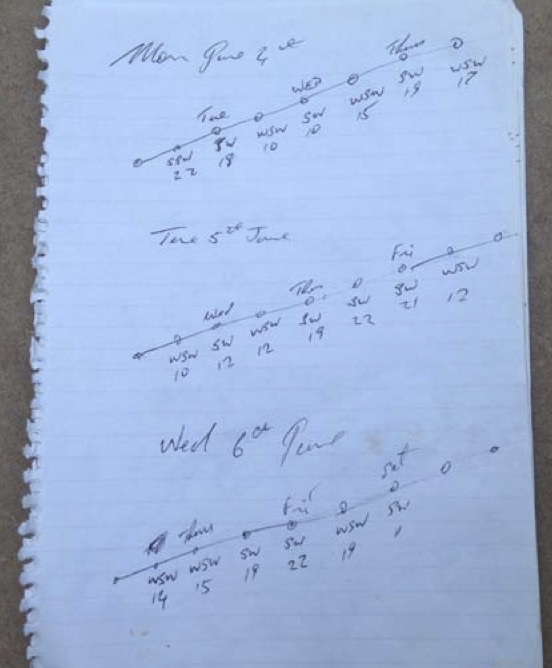

On the first leg of our trip Sean came up with a very practical method for obtaining offshore weather forecasts which became critical to the success of the whole venture. One or two phone calls to his wife Mary back in Ireland and she was quickly up to speed. Now Mary who is not a sailor, would be the first to admit that she is not a meteorologist either, although she would make a sensational TV weather girl.

The routine was that we would trigger our SPOT satellite position report every morning at 1000 Bahamas time and the boats position was automatically forwarded to a predesignated list of email addresses. Mary was on the list and on receipt, she would check the position on an electronic chart, figure out roughly what speed we were doing and what distance we were covering in a twelve hour period. She would then pull down onto her electronic chart the latest grib files showing a pattern of wind direction and speed arrows over our intended sailing ground for the next three days.

If we were covering say 40 miles towards our destination every twelve hours, she would run the grib file model forward twelve hours on her display and note the wind speed and direction at a point 40 miles along the track, run the model forward another twelve hours and note the wind speed and direction 80 miles along the track and so on to cover a three day period. (The twelve hour periods would correspond roughly with midnight and noon ship time.)

Then it was simply a matter of Mary sending us a short emailed text message with the weather data via the satphone. We in turn would then acknowledge receipt on SPOT with an alternate pre-designated message which went only to her own email address. The procedure had the additional advantage of a verified two way check- in every day and it was "free" in that the messages were included in the monthly bundle from the satellite service provider.

The message came to us in the following format e.g.: SW7 S10 SSW9 SW13 W17 W22 NW20. The decode was simple- At midnight tonight it would be Southwesterly 7 knots, at noon tomorrow Southerly 10 knots, at midnight tomorrow South-southwesterly 9 knots ........etc.

The message came to us in the following format e.g.: SW7 S10 SSW9 SW13 W17 W22 NW20. The decode was simple- At midnight tonight it would be Southwesterly 7 knots, at noon tomorrow Southerly 10 knots, at midnight tomorrow South-southwesterly 9 knots ........etc.

We would then simply plot it on a piece of paper and factor the information into our passage planning accordingly. There was only one little issue with the accuracy which Hud back in Marsh Harbour had tipped us off about - add 5 knots when the wind was getting into the high teens and above and he was dead right.

Sean kept the weather reports coming when he got back to Ireland and they were absolutely invaluable . All the more so as we could pick up nothing at all on the two HF receivers on board. A real plus about the whole thing was that we could very quickly and simply validate the accuracy of the forecast against the actual weather. This gave us the confidence over time to rely entirely on their accuracy which in turn gave added comfort over a whole range of issues like fuel and provisions management, navigation and of course general safety. - Everything a blue water sailor needs really. After all, we are supposed to be enjoying ourselves out there.

Tropical Storm Beryl:

When Tropical Storm Beryl threatened to come right over the top of us, Sean worked out the forecast along various alternative routes and sent the results in a single message. We now had all the information we needed.

We were looking at more than 50 knots corrected wind speed along the direct route to the Azores so that was not an option. 47 knot winds were in prospect if we went due east, not what you want in a small boat far out into the Atlantic Ocean.

We headed SE and got exactly the corrected forecast figure of 35 knots when our worst of it hit and we were dry and comfortable. A difference of 12 knots from the easterly option doesn't sound that much. 12 knots is a good wind at any time but when you throw a full gale on top, now thats a big difference.

I am confident the boat could and would have handled all of the above if necessary. However, the object of the whole exercise is to get home, not get hammered.